Part of our African-American Landmarks & Destinations Family Travel Series

By Kimberly Dijkstra

Her name synonymous with the Underground Railroad, Harriet Tubman spent her whole life helping others. Born Araminta Ross to enslaved parents in 1822, “Minty,” as she was known at the time, spent her childhood in Dorchester County, Maryland, and took care of her younger siblings.

“I grew up like a neglected weed – ignorant of liberty, having no experience of it,” she once said.

Minty worked several strenuous jobs and suffered a serious head injury in her teen years that led to painful headaches and seizures for the rest of life. She interpreted the resulting visions and vivid dreams as revelations from god, which propelled her to have a passionate religious faith.

She changed her name to Harriet Tubman upon marrying a free Black man named John Tubman in 1844. Five years later, Tubman’s enslaver died and she was likely to be sold and sent away from her family. She used this opportunity to escape slavery via the network of free and enslaved Blacks, white abolitionists, and other activists known as the Underground Railroad.

Traveling by night and guided by the North Star, Tubman evaded slave catchers, relying on her personal ingenuity and the assistance of conductors on the railroad. When she crossed into Pennsylvania, a free state, Tubman later recalled the experience:

“When I found I had crossed that line, I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person. There was such a glory over everything; the sun came like gold through the trees, and over the fields, and I felt like I was in Heaven.”

In Philadelphia, Tubman worked odd jobs and saved money with the intention of helping her family escape slavery. While the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 pushed more and more former slaves north to Canada, Tubman went to Baltimore to rescue her niece and her niece’s children. The following year, she guided other family members to safety, and in 1851 she returned to Dorchester County to find her husband. Though devastated to discover that he had remarried, Tubman guided a group of other enslaved people all the way to Philadelphia.

Tubman coordinated with abolitionist and former slave Frederick Douglass during this time. Over the next 11 years, she returned to Maryland approximately 13 times, rescuing about 70 slaves, and earned the nickname of “Moses.” She later told an audience:

“I was conductor of the Underground Railroad for eight years, and I can say what most conductors can’t say – I never ran my train off the track and I never lost a passenger.”

In 1859, Tubman bought a piece of land in Auburn, New York, a city known for antislavery activism. The following year she conducted her last rescue mission. Though her story could have ended there, Tubman continued her lifelong pursuit of justice and freedom for others. She served as a spy, scout, nurse, and cook during the Civil War, taking on dangerous duties such as nursing soldiers with smallpox and scouting behind Confederate lines.

The Emancipation Proclamation was an important step in the liberation of enslaved people. In 1863, Tubman became the first woman to lead an armed assault during the Civil War. Alongside Colonel James Montgomery, she led an assault on plantations along the Combahee River. The raid rescued more than 750 slaves and significantly weakened the Confederate economy.

Though her story, again, could have ended there, Tubman continued to work for Union forces, Following the war, she returned to Auburn and, unable to obtain a government pension, struggled through poverty. She married again in 1869 and later adopted a baby with her husband, Nelson Davis.

Tubman spent her later years devoting her passions to women’s suffrage. She worked alongside Susan B. Anthony and Emily Howland, who were both heavily involved in the women’s rights movement, and gave speeches in New York, Boston, and Washington DC to promote the cause.

The extreme headaches resulting from her childhood head trauma continued to plague her throughout her life and she even underwent brain surgery in the late 1890s to help alleviate her suffering. Forever fighting for human rights and dignity, in 1908, Tubman and the AME Zion Church opened the Harriet Tubman Home for the Elderly, which she herself became a patient of in 1911.

Tubman passed away in 1913 at the age of 91 and she was buried at Fort Hill Cemetery with military honors. Her accomplishments have inspired generations of African Americans.

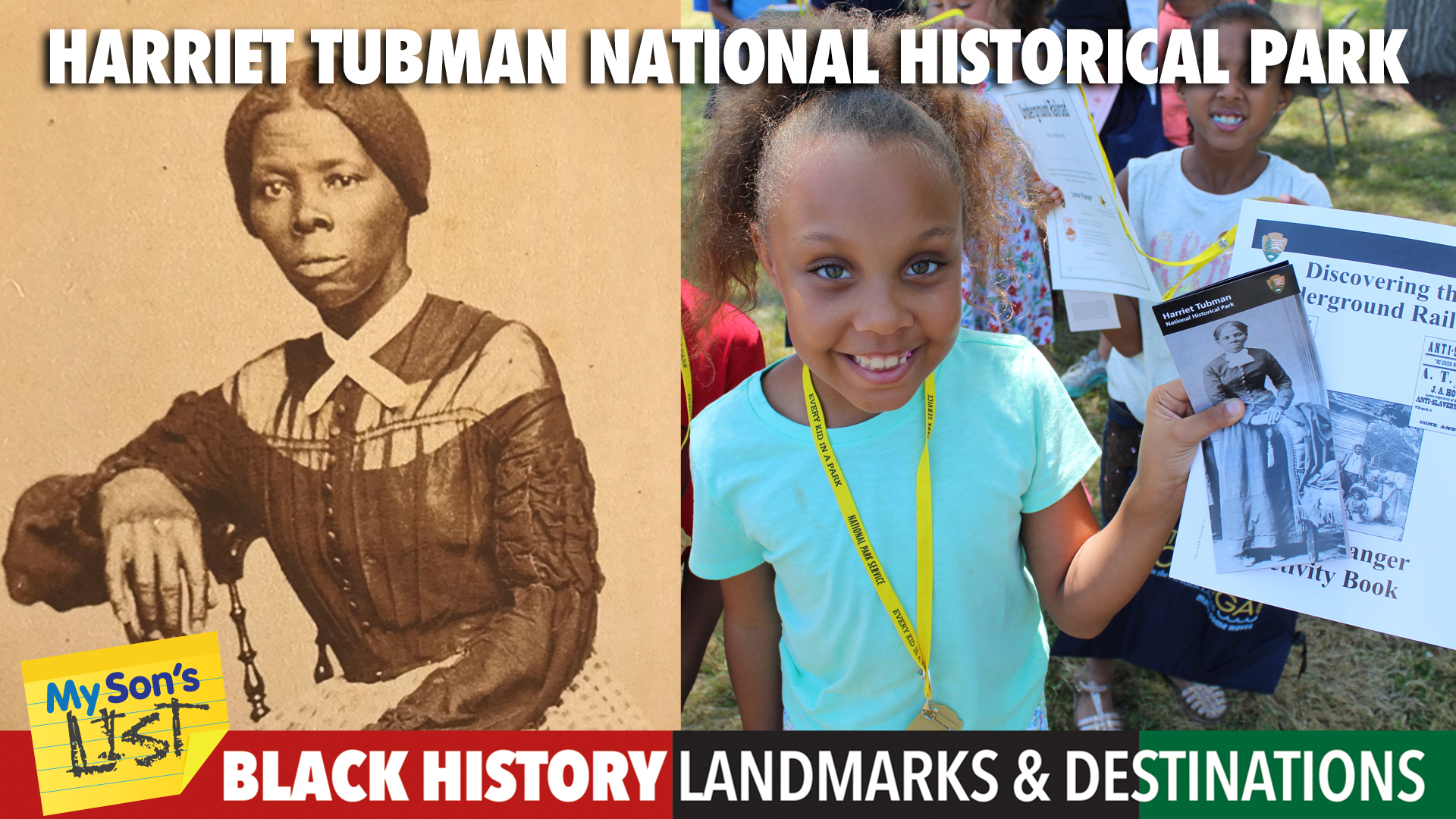

In 2017, Tubman’s residence in Auburn, the Harriet Tubman Home for the Aged, and the Thompson AME Zion Church were designated the Harriet Tubman National Historic Park. The 32-acre campus is jointly operated by the National Park Service and Harriet Tubman Home, Inc., a nonprofit.

The Harriet Tubman Visitor Center, 180-182 South Street, Auburn, NY 13021, offers guided tours of the property.

Children who visit the park can learn more about the Underground Railroad and Harriet Tubman with the Junior Ranger Activity Booklet, which is full of activities and information about this difficult, yet unique, time in American history.

Nearby, Tubman’s gravesite is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is engraved with the inscription “Servant of God, Well Done.”

To honor her legacy and reflect the diversity of our country, Tubman is set to be featured on the $20 bill, the first Black person ever to be on the face of American paper currency.

More Landmarks and Destinations

Selma to Montgomery Historic Trail

Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial

Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site

Booker T. Washington National Monument

The DuSable Museum of African American History

Sojourner Truth - Monuments To A Monumental Woman